Accounts of the founding of the British Empire once echoed the pages of Boy’s Own, featuring visionaries, armed with a flag, a faith and a funny hat, arriving in exotic lands untouched by civilisation. Overcoming great odds, they would kick-start the regions’ histories, show the locals the proper way to live and extend the imperial pink on the map a few inches before sailing off into the history books. Cook in Australia, Rhodes in Africa, Clive in India: in the popular imagination, the Empire was built by remarkable men, all by themselves.

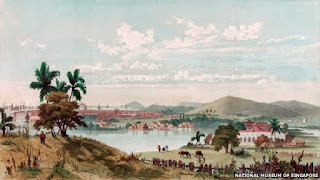

Singapore was no exception — and the myth endures to this day. Stamford Rafflescontinues to dominate its pedestals, revered as the inspired founder who built an international trading enclave from the island swamp at the foot of the Malay peninsula where he disembarked in 1819.

Into this dusty tale Nadia Wright throws a much-needed stick of revisionist dynamite. Raffles is here portrayed as a reckless, inept opportunist, a bully and a hypocrite, who stole the crown from the man actually responsible for building the entrepot. Spare a thought for Raffles’s second-in-command, a tall, gentle Scotsman named William Farquhar.

read more

Singapore history buffs would have heard of Australian writer Nadia Wright’s book, William Farquhar and Singapore: Stepping out from Raffles’ Shadow. It was launched by Professor Tommy Koh, and the British High Commissioner for Singapore in May 2017.

Anyway, news of this unique book about Singapore (a former UK colony) written by a teacher from another ex-colony (Australia) have finally reached the shores of their former colonial masters.

The Spectator, a Conservative weekly news magazine that was published nine years after the modern founding of Singapore (1819, not 1965), published an insightful book review this weekend.

The Spectator Yesterday at 11:21

There are countless memorials to Raffles, but not a single one to the true hero of Singapore, William Farquhar

read more

Stamford Raffles had many sides to him, including being a “psycho” boss to William Farquhar

As the founder of modern Singapore in 1819, Stamford Raffles is often remembered positively for being the one who laid the foundations for the development of our island into a port city.

But author Nadia Wright challenges the dominant narrative and image of Raffles in her new book, William Farquhar: Stepping out from Raffles’s shadow.

In a review of Wright book by the Straits Times, Wright is said to highlight that Raffles had mistreated his subordinate William Farquhar, who was the first British Resident of Singapore in 1819. In fact Wright was quoted saying that Raffles was in fact a “psycho boss”.

read more

Here’s how @therealraffles would behave on social media, unfriend @will.farquhar

Today social media is so entrenched in everyday life that we simply cannot imagine a day without Facebook’s Newsfeed or Snapchat’s Stories. We even train ourselves to talk to each other in 140 characters or less.

But it is precisely in this open environment on the Internet that the most exciting drama plays out.

What if social media existed in the 19th century? How would the drama that was Stamford Raffles’ life play out if it was out on Twitter? We hazard a guess.

read more

1,500 Years Of Singapore’s Ancient History Before Raffles Came Along – The Concise Version

From Sir Stamford Raffles to Yusof Bin Ishak, most of us probably know at least something about Singapore’s past.

Our ancient history, however, somehow seems to be forgotten, left untouched in our old history books. So ask yourself, what really was the foundation of our tiny little red dot?

Let’s take a good look through the centuries to find out.

related: Turns Out, Sir Stamford Raffles Never Thought Much Of Malays

Stamford Raffles’s landing in Singapore

Stamford Raffles landed in Singapore on 28 January 1819. Travelling on the Indiana with a squadron that included the schooner Enterprise, he anchored at St John’s Island at 4.00 pm. The site on the Singapore mainland where Raffles landed is today marked with the statue of Raffles, which is located by the Singapore River behind Parliament House.

The event - Raffles anchored at St John’s Island, but remained on board the Indiana while locals from Singapore island were called aboard. Raffles consulted them, asking if the Dutch had authority over the main island, and noted that only the Temenggong held fort there. The next day, Raffles and William Farquhar landed at a local river (there is a dispute as to whether they landed at Singapore River or Rochor River further east), and visited the Temenggong. Raffles named his landing location South Point.

The Temenggong, a vassal of Sultan Hussein, was consulted and a provisional treaty was agreed upon. Thereafter, the British flag was planted upon Singapore shores, troops were dispatched and instructions left for a fort to be built at what is now known as Fort Canning Hill. Sultan Hussein (Tunku Long) arrived on 1 February, whereupon the trio agreed on a treaty on 6 February. Raffles departed Singapore on 7 February, leaving Farquhar in charge of the inchoate settlement.

read more

1819 Singapore Treaty

On 6 February 1819, Stamford Raffles, Temenggong Abdu’r Rahman and Sultan Hussein Shah of Johor signed a treaty that gave the British East India Company (EIC) the right to set up a trading post in Singapore. In exchange, Sultan Hussein was to receive a yearly sum of 5,000 Spanish dollars while the Temenggong would receive a yearly sum of 3,000 Spanish dollars. It was also on this day that the British flag was formally hoisted in Singapore. It marked the birth of Singapore as a British settlement. Raffles left Singapore the following day, leaving William Farquhar to assume the role of Resident and Commandant in Singapore. The latter’s son-in-law, Francis Bernard, was appointed Master Attendant.

Singapore island before the British - In January 1819, just a month before the treaty was signed, Singapore had approximately 1,000 inhabitants. They were made up mostly of “500 Orang Kallang, 200 Orang Seletar, 150 Orang Gelam and other orang laut”. There were also about 20 to 30 Malays in the Temenggong’s entourage and around the same number of Chinese. This was the Singapore that Raffles and Farquhar found when they first landed on the island. On 30 January, Raffles and the Temenggong signed a preliminary agreement to the establishment of a British trading post on the island. Sultan Hussein, who was in Riau at the time, was then brought to Singapore for the signing of the Singapore Treaty.

Terms of the treaty - The ceremony during which the treaty was signed was attended by the people on the island at the time. Among those present were Chinese planters, Malays, as well as the orang laut. British officials, soldiers and Malay dignitaries at the ceremony dressed in regalia and fine clothes. The treaty was written in English on the left side and Malay on the right. It gave legal backing for the EIC to “maintain a factory or factories on any part of His Highness’s hereditary Dominions”. The British pledged to assist the Sultan in the event of external attacks but not to get involved in internal disputes. The Sultan, in turn, agreed to protect the EIC against enemies. The Sultan and Temenggong also agreed that they would “not enter into any treaty with any other nation … nor admit or consent to the settlement in any part of their Dominions of any other power European or American”. Thus, the treaty protected the interests of both the British and the Malay rulers.

read more

Founding of modern Singapore

In 1818, Raffles managed to convince Lord Hastings, the then governor-general of India and his superior in the British East India Company, to fund an expedition to establish a new British base in the region, but with the proviso that it should not antagonise the Dutch. Raffles then searched for several weeks. He found several islands that seemed promising, but were either already occupied by the Dutch, or lacked a suitable harbor. Eventually Raffles found the island of Singapore. It lays at the southern tip of the Malay peninsula, near the Straits of Malacca, and possessed an excellent natural harbor, fresh water supplies, and timber for repairing ships. Most importantly, it was unoccupied by the Dutch.

Raffles' expedition arrived in Singapore on 29 January 1819 (although they landed on Saint John's Island the previous day). He found a small Malay settlement at the mouth of the Singapore River, headed by a Temenggong (governor) for the Sultan of Johor. The Temenggong had originally moved to Singapore from Johor in 1811 with a group of Malays, and when Raffles arrived, there were an estimated 150 people governed by the Temenggong, mostly of them Malays, with around 30 Chinese. Although the island was nominally ruled by Johor, the political situation was precarious for the Sultan of Johor at the time. The incumbent Sultan of Johor, Tengku Abdul Rahman, was controlled by the Dutch and the Bugis, and would never agree to a British base in Singapore. However, Abdul Rahman was Sultan only because his older brother, Tengku Hussein, also known as Tengku Long, had been away in Pahang getting married when their father died. Hussein was then living in exile in the Riau Islands.

The Singapore Treaty - With the Temenggong's help, Raffles smuggled Tengku Hussein to Singapore. He offered to recognize Hussein as the rightful Sultan of Johor, and provide him with a yearly payment; in return, Hussein would grant the British East India Company the right to establish a trading post on Singapore. In the agreement, Sultan Husain would receive a yearly sum of 5,000 Spanish dollars, with the Temenggong receiving a yearly sum of 3,000 Spanish dollars. This agreement was ratified with a formal treaty signed on 6 February 1819, and modern Singapore was born.

read more

Sir Stamford Raffles Was a Monster. So What?

Do you have a boss who takes credit for everything? You know, the kind who’s never around to help but always present when the champagne pops?

Does the guy praise you in public, only to whisper ‘child-molester’ behind your back? Is he also an incompetent jackass who criticizes everything you do but is incapable of owning his own mistakes?

If the answer is ‘yes’, take heart because William Farquhar had such a boss too. His name was no other than Sir Stamford Raffles—full-time national hero and part-time sociopath.

read more

Stamford Raffles

Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles

Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, FRS (6 July 1781 – 5 July 1826) was a British statesman, Lieutenant-Governor of British Java (1811–1815) and Governor-General of Bencoolen (1817–1822), best known for his founding of Modern Singapore.

He was heavily involved in the conquest of the Indonesian island of Java from Dutch and French military forces during the Napoleonic Wars and contributed to the expansion of the British Empire. He was also an amateur writer and wrote a book, The History of Java (1817).

Raffles was born on the ship Ann off the coast of Port Morant, Jamaica, to Captain Benjamin Raffles (d. June 1797) and Anne Raffles (née Lyde). His father was a Yorkshireman who had a burgeoning family and little luck in the West Indies trade during the American Revolution, sending the family into debt.

read more

Stamford Raffles's career and contributions to Singapore

Thomas Stamford Raffles is famously known as the founder of modern Singapore. Besides signing the treaty with Sultan Hussein Shah of Johor on 6 February 1819 that gave the British East India Company the right to set up a trading post in Singapore, Raffles made several other contributions that helped establish Singapore as a thriving settlement.

Founding of Singapore - In December 1818, Raffles left Calcutta in search of a new British settlement to replace Malacca. Malacca was one of the many British territories returned to the Dutch under the Treaty of Vienna. Raffles had foreseen that without a strategic British trading post located within the Straits, the Dutch could gain control of Straits trade. Raffles arrived in Singapore on board the Indiana on 29 January 1819. Accompanied by William Farquhar and a sepoy, he met Temenggong Abdul Rahman to negotiate for a British trading post to be established on the island. On 6 February 1819, Raffles signed an official treaty with Sultan Hussein and the temenggong and on this day, the Union Jack was officially hoisted in Singapore.

Raffles Town Plan (Jackson Plan) - Raffles conceived a town plan to remodel Singapore into a modern city. The plan comprised the formation of separate clusters to house the different ethnic groups, and the provision of facilities such as roads, schools and land for government buildings. In October 1822, a Town Committee was formed by Raffles to oversee the project. This committee comprised Captain Charles Edward Davis of the Bengal Native Infantry as president, civil servant George Bonham and merchant A. L. Johnston. Lieutenant Philip Jackson was tasked to draw up the plan according to Raffles’s instructions, and the resultant plan was published in 1828.

read more

William Farquhar

The Honourable William Farquhar

Major-General William Farquhar (/ˈfɑːkər/ FAH-kər; 26 February 1774 – 11 May 1839) was an employee of the East India Company, and the first British Resident and Commandant of colonial Singapore.

Farquhar was born at Newhall, Aberdeenshire, near Aberdeen in 1774 as the youngest child of Robert Farquhar and Agnes Morrison, his father's second wife. His brother, Arthur, two years his senior, rose to the rank of rear admiral in the Royal Navy, and received a knighthood for his distinguished services during the Napoleonic Wars.

Farquhar joined the East India Company as a cadet at age 17. Shortly after arriving in Madras on 19 June 1791, he was promoted to a low-rank commissioned officer of the Madras Engineers on 22 June 1791. Two years later, on 16 August 1793, he became a lieutenant in the Madras Engineers.

read more

William Farquhar

Major-General William Farquhar was the first British Resident and Commandant of Singapore from 1819 to 1823. In January 1819, Farquhar accompanied Sir Stamford Raffles on a mission which led to the establishment of a British trading post in Singapore. Raffles left Singapore shortly after and the new trading post was placed under the charge of Farquhar. Although in the ensuing years, Farquhar and Raffles disagreed over the administration of the settlement and Farquhar was dismissed in 1823, he made many important contributions to Singapore’s early growth and development.

Early life - Born in 1774, Farquhar entered the service of the East India Company (EIC) in 1791 at the age of 17 as a cadet in the Madras military establishment. He arrived in Madras on 19 June 1791, became an ensign in the Corps of Madras Engineers on 22 July, and was promoted to lieutenant two years later on 16 August 1793.

Activities in Malacca - Farquhar was appointed engineer-in-charge of a party of Madras Pioneers in the expeditionary force that captured Melaka from the Dutch on 18 August 1795. On 1 January 1803, he was promoted to the rank of captain, and on 12 July the same year, he was appointed commandant of Melaka. He was made a major-in-corps on 26 September 1811. In December 1813, in recognition of his dual duties as the civilian and military authority in Melaka, his designation was revised to Resident and Commandant of Melaka, a position he held for several years until the return of the Dutch in September 1818. During his tenure, he assisted in missions in the region, including the British invasion of Java led by Governor-General Lord Minto and Sir Stamford Raffles in August 1811.

read more

The William Farquhar Collection of Natural History Drawings

Prior to his tenure as Singapore’s first Resident and Commandant, William Farquhar served as Resident and Commandant of Melaka from 1803 to 1818. During this period, he made several important botanical and zoological discoveries, and amassed a sizable collection of natural history drawings. Painted by local artists Farquhar had commissioned, these watercolours depict the diverse flora and fauna of the Malay Peninsula.

These 477 drawings have since found their way back to Singapore through Mr Goh Geok Khim, who purchased and donated the complete set to the National Museum of Singapore. This year, The William Farquhar Collection of Natural History Drawings finds its permanent home in The Goh Seng Choo Gallery, named in honour of Mr Goh’s late father.

The gallery will feature a rotating selection of the drawings presented in their original 19th century colonial context of exploration and discovery, experimental gardening, and Farquhar’s own contribution to the art and science of natural history.

read more

William Farquhar Collection of Natural History Drawings

Top left: gambier; top right: black pepper; bottom left: wild nutmeg (Gymnacranthera farquhariana); bottom right: durian

The William Farquhar Collection of Natural History Drawings consists of 477 watercolour botanical drawings of plants and animals of Malacca and Singapore by unknown Chinese (probably Cantonese) artists that were commissioned between 1819 and 1823 by William Farquhar (26 February 1774 – 13 May 1839). The paintings were meant to be of scientific value with very detailed drawings, except for those of the birds which have text going beyond their original purpose. For each drawing, the scientific and/or common name of the specimen in Malay, and, occasionally, in English, was written in pencil. A translator also penned the Malay names in Jawi using ink. The paper used was normally European paper framed by a blue frame while some have no frames at all suggesting there are two artist.

During his tenure as Resident and Commandant of Singapore, Farquhar hired a group of professionally trained Chinese artists from Macau (as described by Munshi Abdullah ) to paint watercolours of the flora and fauna of the Malay Peninsula. Farquhar donated these in eight volumes to the Museum of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland on 17 June 1826. In 1937, the Society lent six of the volumes to the Library of the British Museum (Natural History) (now the Library of the Natural History Museum), retaining the two volumes of botanical drawings in its own library.

In 1991 the Natural History Museum returned the works to the Society for valuation, and on 20 October 1993 the Society offered them for sale by auction at Sotheby's in London, where they were acquired by Goh Geok Khim, founder of the brokerage firm GK Goh, for S$3 million. Goh donated the drawings to the National Museum of Singapore in 1995. As at 2011, the collection was believed to be worth at least $11 million. In 2011, 70 works from the collection were placed on permanent display in the Goh Seng Choo Gallery of the museum, named for Goh's father

read more

Singapore at 50: From swamp to skyscrapers

Fifty years ago Singapore became an independent state, after leaving the short-lived Malaysian Federation. With no natural resources, just how did this tiny country go from swamp to one of the region's leading economies? On the strength of its human resources - immigrants like my grandfather.

At the age of 17, with only the shirt on his back, Fauja Singh left his parents in a small Punjabi village and made the long and dusty journey on foot and by train to Kolkata (Calcutta), where he caught a ship to his new home. It was the early 1930s. He arrived in a melting pot of cultures and chaos on an island at the mouth of a river, which bustled with trade - Singapore.

Once a swamp-filled jungle, when the British arrived in 1819, under the leadership of Sir Stamford Raffles, the makings of modern Singapore began. Lying at the mid-point of the shipping route between India and China, it became a thriving trading port, and with this trade came a huge influx of immigrants from all over Asia.

read more